“Touching the Time” in the Mercati di Traiano in Rome

Lucrezia Ungaro Director of Mercati di Traiano, Museo dei Fori Imperiali

“Toccare il Tempo” nei Mercati di Traiano, a Roma

“Toccare il tempo”. Si può “toccare” il tempo?

Il titolo della mostra di sculture di Kan Yasuda è estremamente suggestivo. Poetico. Immateriale. Evocativo.

Razionalmente, inaccettabile: il verbo “toccare” indica un’azione rivolta a qualcosa di tangibile, mentre il tempo è, per eccellenza, immateriale.

Allora, questa associazione tra un verbo materiale e una dimensione intoccabile indica un rapporto di comunicazione, di superamento di un confine.

Resta l’interrogativo iniziale, e ci si chiede la ragione profonda che ha spinto il maestro Kan Yasuda a scegliere questo titolo.

E quali potranno essere le risposte dell’artista, e dei suoi diretti interlocutori, ovvero i visitatori che saranno attratti, o, anche respinti, da questa immagine.

Innanzitutto, la provenienza dell’artista.

Il maestro Kan Yasuda viene dal Giappone e ha ambientato le sue opere nei giardini verdi e azzurri del lontano Paese del Sole.

Il contesto, quindi, sono gli spazi della natura senza età, senza tempo:

il suolo della madre terra sulla quale sono poggiati pesante “sassi” di metallo argento, gli specchi immobili d’acqua sui quali si riflettono ciottoli candidi e levigati, i tappeti erbosi estesi fino all’orizzonte e tagliati verticalmente da stradine bianche che portano a strutture squadrate monumentali, ma aperte di nuovo sul verde infinito.

Terra-cielo, elementi senza tempo.

Gli spazi chiamano le forme.

E le opere sono forme pure, arrotondate, terse, levigate dal tempo, rese incontaminate dal tempo che scorre su di esse; o squadrate, dure, angolose, come le masse monolitiche della terra, ma provviste di aperture, strette fessure o finestre allungate, che liberano la materia nello spazio, ne sprigionano l’essenza dal blocco chiuso.

Si alternano il colore bianco del marmo, e il colore scuro del metallo, reso luce brillante, e accecante, dai raggi del sole.

Toccare la superfice delle opere permette di percepire la consistenza della materia, il lavoro dell’uomo;

sedersi o sdraiarsi su alcune di esse fa sentire il rapporto fisico tra il nostro corpo e le linee che la materia ha preso, plasmata dall’artista.

Per trovare il candore del marmo statuario, Kan Yasuda si è recato a Pietrasanta, nella zona dove la materia preesistente all’uomo viene estratta e lavorata dall’uomo per diventare oggetto.

E il paesaggio e la materia del Paese del Sole occidentale hanno prodotto altre forme, altri legami corporei tra la forma e lo spazio e, soprattutto, tra lo spazio, che diventa luogo, e l’uomo.

Le sculture sono sempre ideate per essere all’aperto:

ma dalla dimensione unica della natura in Giappone, l’artista passa a concepire le opere per i contesti abitativi:

in Italia, lo spazio è antropologizzato, l’uomo è il centro dell’universo e ha costruito le città.

Le “sculture all’aperto”, dunque, divengono “sculture nella città”.

E le città maggiormente emblematiche in Italia sono:

Firenze, il centro per eccellenza dell’architettura e della cultura del Rinascimento, l’età dell’Uomo.

E Roma, l’urbe, la città degli imperatori e dei papi, la città su cui tutti misurano se stessi solo quando sono nella piena maturità, e si sentono pronti tanto da non esserne schiacciati.

E, a Roma, le opere di Kan Yasuda vengono accolte nei Mercati di Traiano, nel complesso di edifici che si alza dal livello del suolo verso il cielo, adagiandosi sulle pendici del Quirinale e nascondendo con le ardite soluzioni architettoniche il taglio nella roccia operato dai Romani per ottenere altro spazio per il monumentale Foro di Traiano.

Uno spazio mutato, dunque, prepotentemente adattato e modellato dagli antichi, in funzione dello spazio pubblico per eccellenza degli uomini, il foro.

Infine, il contesto della mostra: i Mercati di Traiano a Roma.

Kan Yasuda non ha voluto critici che parlino della mostra.

Ha voluto il luogo: i Mercati di Traiano.

Il complesso di edifici, che si articola su sei livelli secondo una disposizione altovolumetrica movimentata in forme emisferiche e squadrate, è aperto verso la città e comunica con essa.

Scomposto, trasformato, rifunzionalizzato, riaggregato, ora restaurato secondo le metodologie più moderne, ma con le tecniche e i materiali delle maestranze romane, è sempre stato parte del contesto urbano.

Ha attraversato il tempo, ne è stato toccato, lo ha toccato.

Ed è diventato punto di riferimento spaziale e concettuale per l’arte di questo tempo.

Peter Erskin ha giocato con la luce sulle sue murature, spezzandola in arcobaleni sul rosso dei laterizi;

Anthony Caro ha inserito le sue opere negli ambienti secondo il criterio di continuità tra gli spazi e le forme;

Richard Serra ha isolato volumi pieni e squadrati nello spazio monumentale della Grande Aula;

Eliseo Mattiacci ha riprodotto le volte e le concavità dell’architettura romana con sfere sospese e sparse sul suolo;

Igor Mitoraj ha esposto statue colossali antiche ridotte a frammenti tra le architetture frammentate dal tempo;

Christoph Bergmann ha proiettato nel futuro figure di dei di uomini del passato.

E ora, Kan Yasuda.

Che ha collocato le sue sculture, dai nomi che richiamano il tempo racchiuso in scatole, contenitori, gocce, lungo il percorso esterno che si snoda dal livello del Foro di Traiano al piano del Giardino delle Milizie, facendo attenzione che comunichino con il monumento, tra loro, con la città.

Ogni posizionamento di opera ha richiesto tempo, e cura.

La scultura non era solo “allestita; doveva entrare in simbiosi con lo spazio, doveva rapportarsi con gli orizzonti,

doveva seguire, costruire e intrecciare assi visibili.

Il maestro aveva presentato più progetti espostivi, nel tempo; e nel corso d’opera ha avuto ripensamenti, ha isolato opere, ha cercato la disposizione chiastica e asimmetrica, lineare e frazionata in piani, varia, mutevole, ma ferma e assoluta nell’interrelazione con il luogo.

Uno degli spazi privilegiati è, significativamente, la strada, creazione dell’uomo destinata a superare il tempo.

Il monolite Uomo e terra emerge dai basoli della via Biberatica antica, come una creatura primordiale, del tempo in cui non esisteva ancora la figura, ma solo la forma, ovaleggiante e convessa come la forma dei basoli di lava.

La stele mossa da concavità Nascita, posta all’angolo sud della via basolata che divide il Grande Emiciclo dal Foro di Traiano, è orientata in modo da accogliere, come nel grembo materno, la luce generatrice del Sole e la luce fredda della luna.

Le due candide porte Tensei/Tenmoku inquadrato l’asse rettilineo della moderna via Alessandrina e suggeriscono al passante la sosta, il passaggio, la fotografia al compagno incorniciato entro quella aperta, così fissato nella memoria.

Un altro spazio importante è la terrazza, che si affaccia sul monumento e sulla città, e che accoglie opere che a loro volta accolgono il visitatore, lo invitano al passaggio attraverso le loro aperture illusorie in uno spazio sempre esterno, aperto sui diversi lati verso la città:

Chiave del sogno, Porta del ritorno, Ascoltare sono volontariamente visibili da ogni angolazione e da ogni livelli, e rifrangono la luce sulle superfici levigate e brillati.

Infine, l’interno. Sempre inteso come un’apertura verso l’esterno.

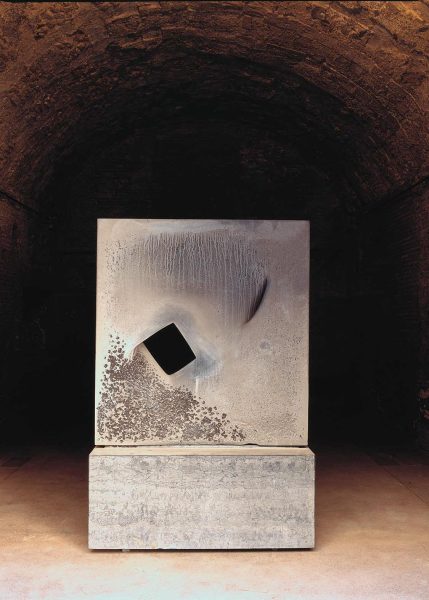

Nel blocco squadrato dell’opera Niente esiste è riprodotta la forma della taberna in cui essa è marmo nero del Belgio in cui è realizzata assorbe I colori del buio, evocato dalla scala che sale dalla cantina rinascimentale, e si trasmette nella mancanza di luce degli incavi, per essere infine catturato dalle fessure nell’opera e respinto, disperoso verso l’esterno, nella luce, nel tempo.

Allora, si può rispondere alla domanda iniziale “Si può toccare il Tempo?” ai Mercati di Traiano, con le opere di Kan Yasuda, sì.

Lucrezia Ungaro

Direttrice, Museo dei Fori Imperiali

“Touching the Time” in the Mercati di Traiano in Rome

“Touching the Time”. Is it possible to “touch” the time?

The title of the exhibition of sculptures

by Kan Yasuda is extremely poetic. Immaterial. Evocative.

Rationally unacceptable the verb to

touch indicates an action directed

at something tangible,

while time is quintessentially immaterial.

So this association between a material verb

and an untouchable dimension indicates

a relationship of communication,

of transcending of a boundry.

The initial question remains,

and we wonder about the deep reason

that has prompted master Kan Yasuda

to choose this title.

And what the artist’s answers might be;

and those of his direct interlocutors,

that is, the visitors who will be attracted

– or even repelled – by this image.

First of all, the artist’s origin.

Master Kan Yasuda comes from Japan,

and he has set his works in the green

and blue gardens of the Land of the Rising Sun.

The context, therefore,

is the spaces of ageless,

timeless nature :

the land of mother earth,

placed on which are silvery metal “stones”,

the immovable mirrors of water on which white,

smooth pebbles are reflected,

the grassy carpets stretching to the horizon

and cut vertically by white roads that

lead to monumental square structures,

but open onto the endless greenery.

Earth-sky, timeless elements.

The spaces call the forms.

And the works are pure, rounded, clear forms, smoothed by time,

rendered uncontaminated by the time that flows over them;

or square, hard, angular, like the monolithic masses of the earth,

but with openings, narros cracks or elongated windows,

freeing the material in space, releasing its essence from the closed block.

The white colour of the marble

and the dark colour of the metal alternate;

hey are made bright and blinding by the rays of the Sun.

Touching the surface of the works allows you

to perceive the substance of the material,

the work of man;

sitting or lying on some of them

makes you feel the physical relationship

between our bodies and lines that the material has taken on,

shaped by the artist.

To find the whiteness of the statuary marble,

Kan Yasuda moved to Pietrasanta,

the area where the material

from before the existence of man is extracted and worked

by man to become an object.

And the landscape and material of the western Land

of the Sun have produced other forms,

other corporeal connections between form and space,

and, above all, between the space that becomes location and man.

Sculptures are always conceived to be in the open air:

but from the unique dimension of nature in Japan

the artist goes on to conceive the works for home contexts:

in Italy, the space is anthropologized,

man is the centre of the universe and has built the cities.

“Open-air sculptures”, therefore, become, “sculptures in the cities”.

And the most emblematic cities in Italy are:

Florence, the centre par excellence of the architecture

and culture of the Renaissance,

the age of Man. And Rome, the urbe, the city of emperors and popes.

The city against which all measure themselves,

but only when they are in full maturity,

and feel ready to not be crushed by it.

And, in Rome,

the works of Kan Yasuda are welcomed in the Mercati di Traiano.

In the complex of buildings that

rise from ground level towards the sky,

stretching out onto the slopes of the Colle Quirinale

and hiding with clever architectural solution the cutting into the rock

by the Romans to obtain further space for the monumental Foro di Traiano.

A changed space, therefore,

forcefully adapted and modelled by the ancients,

to suit the public space par excellence of men, the forum.

Finally, the contexted of the exhibition:

the Mercati di Traiano in Rome.

Kan Yasuda does not want critics to talk about the exhibition.

He wants the location to do it:

the Mercati di Traiano.

The complex of buildings that,

structured over six levels,

according to a lively three-dimensional plan

in hemispherical and square forms,

opens towards the city and communicates with it.

Decomposed, transformed, re-functionalised, re-aggregated,

now restored according to the most modern methodologies

but with the techniques and materials of Roman workmen,

it has always been part of the urban context.

It has traversed time,

it has been touched by time;

time has touched it.

And it has become the spatial

and conceptual point of reference for the art of this time.

Peter Erskine has played with light on his walls,

breaking it up into rainbows on the red of the tiles;

Anthony Caro has inserted his works

into the environments following the criterion of continuity

between spaces and forms;

Richard Serra has isolated full,

square volumes in the monumental space of Grande Aula;

Eliseo Mattiacci has reproduced the vaults

and concavities of Roman architecture

with spheres suspended and spread over the ground;

Igor Mitoraj has exhibited colossal ancient statues reduced

to fragments amid the architectures fragmented by time;

Christoph Bergmann has projected figures

of the gods and men of the past into the future.

And now, Kan Yasuda, Who has placed his sculptures,

with names that recall time contained in arks and drops,

along the outdoor path that winds from the level of the Foro di Traiano

to the level of the Giardino dell Milizie,

taking care to ensure that they communicate with the monument,

with each other, with the city.

The positioning of every work has required time and care.

The sculpture was not just “laid out”.

It had to enter into symbiosis with the space;

it had to establish a relationship with the horizons;

it had to pursue, construct and weave together visual axes.

Over time the master had presented a number of projects for exhibitions:

and during the course of the work he has had second thoughts,

he has isolated works,

he has sought chiastic and asymmetrical arrangements,

linear and scattered on the grounds, varied, mutable,

but steady and absolute in their interrelation with the location.

Significantly, one of the privileged spaces is the road,

man’s creation destined to go beyond time.

The granite monolith Man and earth emerges

from the paving stones of the ancient

Via Biberatica like a primordial creature,

from the time when the figure as such did not exist yet,

only the form, oval and convex like the forms of lava.

The stele of a motion out of concavity,

Birth, placed at the southern corner of the paved road

that divides the Grande Emiciclo from the Foro di Traiano,

is oriented so as to hold the generating light of the Sun

and the cold light of the moon,

as in a mother’s womb.

The two white doors called Tensei/Tenmoku frame the rectilinear axis

of the modern Via Alessandrina,

suggesting to the passer-by the idea of stopping,

passing and taking a photograph of their companion framed

within that open space,

thus fixed in memory.

Another important space is the terrace,

which looks onto the monument and the city,

and welcomes works that in turn welcome visitors,

inviting them to walk through their illusory openings into a space

that is always external,

open on the various sides towards the city:

Key of the Dream, Gate of Return, Listen, are intentionally visible

from every angle and form every level,

and refract the light on their smooth,

bright surfaces.

KIMON “Touching the Time”, Roma

Finally, the interior.

Always understood as an opening towards the exterior.

In the square block of the work Nothing Exhists,

the form of the taberna in which it is located is reproduced,

the form of the embedding in the walls is taken up,

while the colour of the black marble

from Belgium of which it is made absorbs the colours of darkness,

evoked by the staircase climbing from the Renaissance cellar,

and is transmitted in the absence of light of the cavities,

to be finally captured by the niches in the work,

repelled and dispersed to the exterior, in light, in time.

So can we respond to the initial question:

“Is it possible to touch time?”

At the Mercati di Traiano,

with the works of Kan Yasuda,

yes, we can.

Lucrezia Ungaro

Director of Mercati di Traiano, Museo dei Fori Imperiali

MUKAYU “Touching the Time”, Roma Photo by Akio Nonaka

▶︎Exhibitions / Touching the Time